Report on the Dispatch to Cameroon: Water Hygiene and Sanitation Conditions Surrounding the Baka and Analysis of the Picture Storytelling

Koji Hayashi

Specially Appointed Research Fellow

The Center for African Area Studies

Kyoto University

I traveled to the Republic of Cameroon from 13th February to 5th March 2025.

Water and Sanitation in Gribé

In Gribé, the first research site, we used the field station (FS) where we had stayed for long periods several times in the past as part of the SATREPS FOSAS project (https://www.jst.go.jp/global/kadai/pdf/h2209_h26.pdf), but it had not been visited for research purposes since 2016. At the water source (locality: Nkoual), which is about 2 km from the field station, it is possible to collect high-quality spring water, but the state of the foothold and water collection area was not good due to the deterioration of the stairs and water tank that had been built around 2014 when I was involved as a member of the FOSAS project. The spring water flows out of the bottom of the water tank, and to fill the tank with water, it is necessary to insert a hose into the water supply hole in the water tank and use water pressure to draw the water that has accumulated at the bottom of the tank, which is time-consuming. In recent years, I have been conducting research on water and sanitation in rural areas of Cameroon’s tropical region, including the Bako community, and I have realized that it is difficult to secure a stable water supply, as well as to store and maintain sanitation facilities that combine safety and convenience over the long term.

The time of year when I visited Cameroon was the height of the dry season. As there is almost no rain, traveling along the unpaved roads is relatively comfortable, but it is also a busy time of year for the Baka people, who are away from their villages for long periods to live in the forest, or who are working to clear new fields or helping the farming people who live nearby. In Gribé, too, there were many households where the Baka had set up temporary living bases deep in the forest, far from the main roads and the village, and were living there with their families. For this reason, the number of Baka we saw around FS was unexpectedly limited.

As part of our survey on the sanitary conditions in the Baka village, we confirmed that we could not find any toilets that the Baka themselves used. Although there are several toilets set up near the houses of the farming and merchant communities that live nearby, the Baka do not use them. We asked several Baka why they did not build their toilets. When we visited Gribé in 2016, we heard that they were not keen on building toilets, and in fact, we got the impression that they had a negative image of building toilets, related to smells and hygiene. This was because it seemed that they did not envy the toilets installed by the neighboring farming community but rather looked down on them. For the Baka people, the fact that toilets are in a place where people can see them may be unnatural. It also seemed that the Baka people, whether consciously or unconsciously, accepted their lifestyle and the buildings that include their homes, including the fact that they do not have toilets, as part of their identity.

As part of the hygiene survey of the Baka, we also interviewed several women about menstruation. The information we obtained was generally the same as that we had obtained in other areas, such as Lomié, and the women said that although they were aware that certain sanitary products (sanitary napkins) existed, they did not buy and use them daily. Gribé is a region that can be called a “town” mainly inhabited by agricultural people, and it is larger than the other villages in the surrounding area. For this reason, there are said to be eight general stores in Gribé. When I visited three of these shops, I found that each of them sold one or two types of sanitary napkins. The prices were slightly higher than those in Yaoundé, ranging from 800 to 1,000 CFA francs (10 napkins per pack; approx. 200 to 250 yen). According to the shopkeepers, “Agricultural people come to buy them, but Baka don’t.” Compared to the local price standards of 500 F (about 125 yen) for a can of sardines and 1,000 F (about 250 yen) for a large bottle of beer, these are considered “luxury goods” for the average baka, who has limited opportunities for earning cash income.

Analysis and Issues Regarding the Picture Storytelling Performance in Lomié

In Lomié, which has been our research base in recent years, we recorded a video of the previous year’s performance of the Picture Storytelling by the Baka storytellers, and with the help of Aleka from the local NGO ASTRADHE and Ambassa from the M village (both Baka), we checked the content of the story and transcribed the words.

In the demonstration of the picture, the story was based on the original text created in the previous year. It was difficult to read the Baka language text accurately while performing, but the narration with the accompanying video images generally followed the content of each picture story. However, some pictures were difficult to convey or understand in terms of nuance. The two performers, Ambassa (a man in his 50s) and Boi (a woman in her 30s) are both eloquent in their daily lives and are also storytellers of the “likano” folktales. During the picture story performance, the audience (mainly children) responded to the performers’ unique interpretations and realistic storytelling, which did not rely on the text. The children listened quietly, focusing on the pictures in the picture story show, but they also laughed at the slightly exaggerated spoken dialogue and the scenes involving excretion. We plan to continue with an analysis of the content of the storytelling in the performance, as well as the production process of the picture story show, and to consider the reactions of the audience.

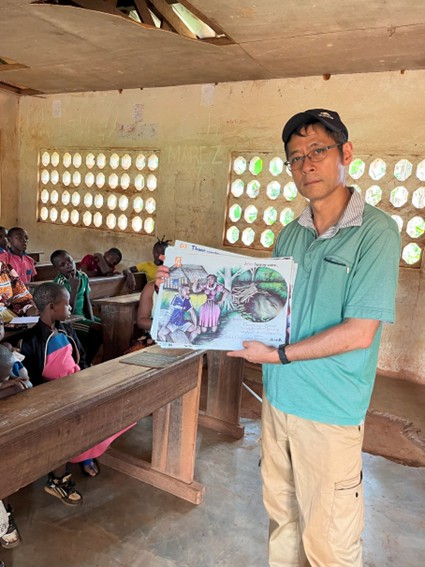

During this stay, the presenter also gave a picture story performance in front of a specially gathered audience of children (both Baka and farming children) and teachers at a public elementary school near the Baka village. At the same time, I also tried to perform in French using the version created by Mr. Mintiet Christoph, who drew the pictures from his perspective the previous year. After the performance, the teacher gave a follow-up in French about the content of the picture story show, and several children made comments about what they had learned from the picture story show. This time, it was an experimental attempt, but I was able to discuss with the teacher that next time, as an approach after the performance, I would like to have an opportunity for the children to draw pictures and have discussions. At the same time, it is also possible to point out that there are many problems with the hygiene situation in the surrounding environment of the elementary school. For example, there are no safe, hygienic water sources or toilets, and it is necessary to continue to consider how we should be involved in improving the actual situation.